By Dayana Melendez

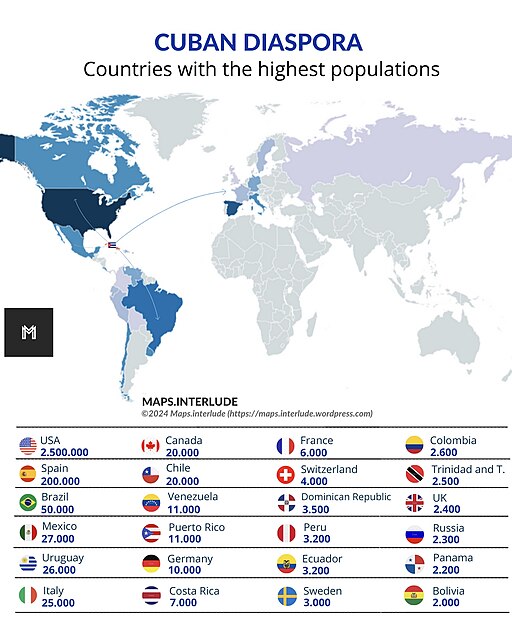

Cuban migration to the United States has surged in recent years, fueled not only by economic hardship but by growing disillusionment with the island’s political system. Among those making the journey are professionals such as doctors, teachers and engineers who once served within Cuba’s state-run institutions but now seek lives defined by freedom and self-determination.

“The root of the problem is in Cuba,” said Sebastián Arcos, interim director of the Cuban Research Institute at Florida International University. “And unfortunately, it’s not changing.”

Arcos calls the current wave of Cuban migration “an explosion,” a response not to external pressure but to what he describes as the internal collapse of a system that has lost its credibility with its own people.

New Migration Policies

Recent shifts in U.S. immigration policy have placed Cuban migration back in the national spotlight. In April 2025, the Department of Homeland Security revoked legal protections for more than 500,000 migrants from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela who had entered the United States under humanitarian parole since October 2022. Of these, about 110,900 were Cuban nationals, with 26,000 who arrived after March 2024 particularly vulnerable as they hadn’t yet qualified for protection under the Cuban Adjustment Act. These changes have paved the way for deportations that, in some cases, are separating families and sending Cubans back to uncertain futures.

“The root of the problem is in Cuba, and unfortunately, it’s not changing.”

Sebastián Arcos

A case in Tampa, Florida, drew widespread attention in April when a Cuban mother, Heidy Sanchez, was deported after entering the country under humanitarian parole. Her 1-year-old daughter, a U.S. citizen by birth, remained in Florida with relatives. Sanchez told Reuters she was given no choice during a routine check-in with immigration authorities and was separated from her still-breastfeeding daughter without warning — an account disputed by the Department of Homeland Security. The separation sparked outrage among immigrant advocacy groups and reignited national conversations about the ethics of deporting parents while their children remain in the U.S.

According to a Reuters report from April 2025, immigration advocates at a rally in Miami expressed concern about the humanitarian consequences of recent deportations. One advocate stated, “We’re seeing families being torn apart and individuals being returned to the same repression they risked everything to escape.” Critics argue that returning migrants to a country with a documented history of political persecution and economic crisis undermines longstanding U.S. commitments to protecting vulnerable populations.

In an interview with NPR, South Florida immigration attorney Mariela Castro said that the reversal of humanitarian parole policies has left many migrants in a precarious position. “Some of these families were on a path to lawful status. Now they’re at risk of removal overnight,” she told NPR. “It’s a drastic change that doesn’t reflect the realities people are fleeing.”

Historic Migration Wave

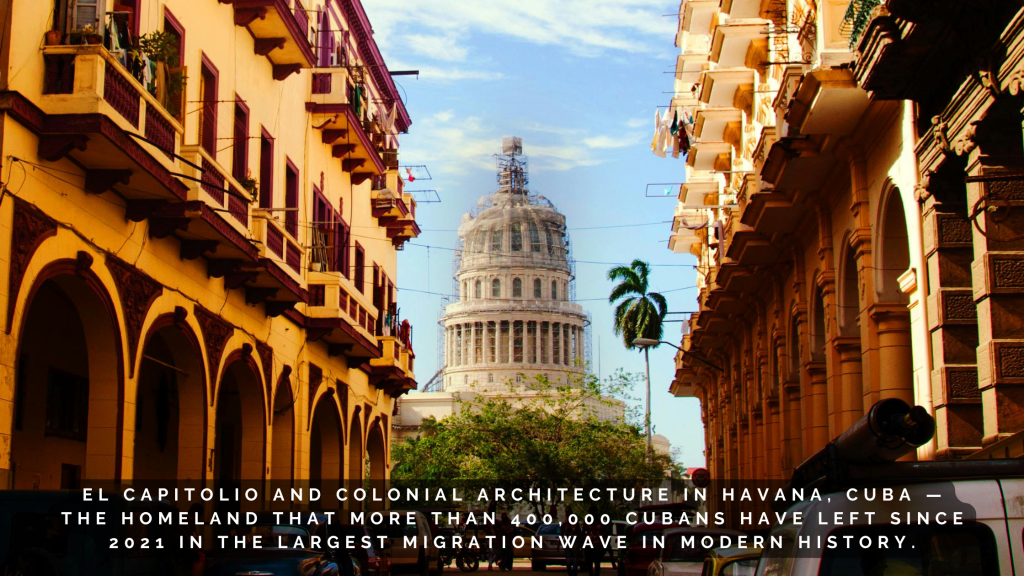

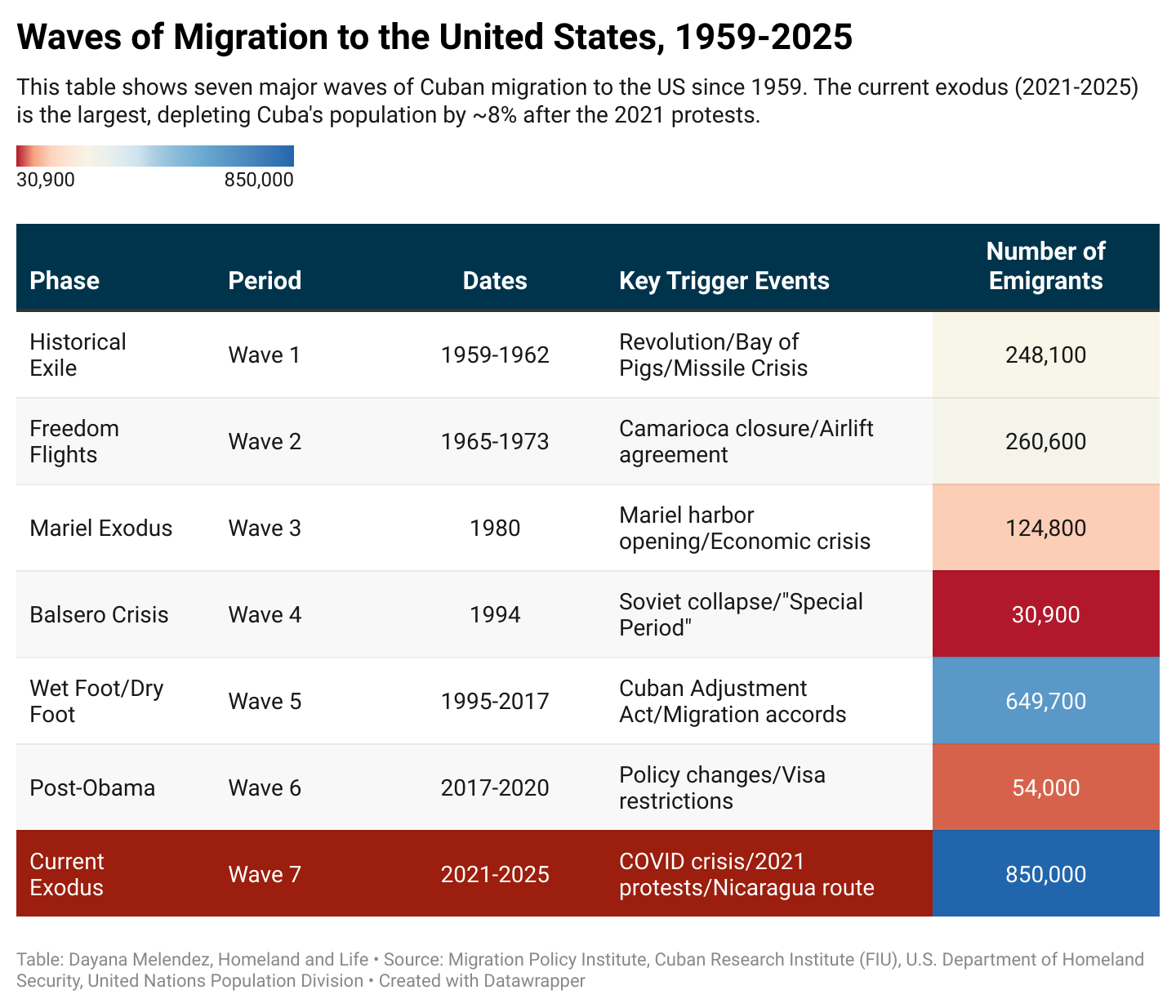

These developments come amid a broader wave of Cuban migration. More than 400,000 Cubans have arrived at the U.S. southern border since 2021, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection, marking the largest surge in modern history. This current exodus far exceeds previous historic Cuban migration waves, including the 1980 Mariel boatlift that brought 125,000 Cubans and the 1994 rafter crisis with approximately 35,000 migrants combined. With political dissent growing and the economy deteriorating, the motivations behind this exodus go far beyond economic desperation.

Patria y Vida and July 11 Protests

On July 11, 2021, widespread demonstrations erupted across the island in the largest protests since the revolution, triggered by shortages of food and medicine, ongoing blackouts, and growing frustration over a lack of civil liberties. The protests were fueled in part by a viral reggaeton anthem, “Patria y Vida,” performed by Cuban artists including Gente de Zona, Yotuel, Descemer Bueno and El Funky.

Grammy Award-winning anthem ‘Patria y Vida’ (2021) – Performed by Yotuel, Descemer Bueno, Gente de Zona, Maykel Osorbo and El Funky.

The song directly challenged the Cuban government’s long-standing revolutionary slogan, “Patria o Muerte,” and became a cultural flashpoint for dissent both on the island and among the diaspora. Thousands took to the streets chanting “Patria y Vida,” a phrase that flipped the state-imposed slogan “Patria o Muerte” — homeland or death — into a call for life. As those demonstrations unfolded, hundreds were arrested. Others quietly made plans to leave.

A System That Pushes Its People Out

For Arcos, who left the communist country at age 31, the journey was shaped by firsthand experience with repression. For many others, particularly defectors like medical professionals, migration is not just about escaping hardship. It is about escaping control.

“There is a deliberate policy of using migration as a tool of statecraft,” Arcos said. “The Cuban regime opens the valves when it suits them: to relieve pressure, to shape international negotiations and to rid themselves of dissenters.”

“The Cuban government has traditionally exported its own dissent,” he added, referencing past exoduses like the Mariel boatlift in 1980 and the 1994 balsero crisis. “It’s a tactic they’ve used for decades to prevent popular explosions inside the country.”

Those targeted for export include doctors, construction workers and technicians sent on foreign missions. Arcos called the practice state-sponsored exploitation, noting that the salaries earned abroad are largely withheld by the Cuban government.

“They use the labor force to generate revenue and as propaganda,” he said. “The narrative is: ‘Look how benevolent the Cuban regime is, helping poor countries.’ But the reality is that they’re exploiting their workers while keeping their families as hostages.”

“The Cuban regime opens the valves when it suits them… to rid themselves of dissenters.”

Sebastián Arcos

He said the practice not only undermines the labor rights of those sent abroad but uses family separation as coercion. “You are being watched. Your family is still on the island. You know the message is clear: Don’t defect, or you’ll pay a price,” Arcos said.

He knows this firsthand. His sister-in-law, a Cuban doctor sent to Africa, defected more than a decade ago. Her husband and children were forced to remain in Cuba for two years before reuniting.

“These are people who have already served the state. And yet when they seek freedom, they are punished by being separated from their loved ones,” he said.

The View From Exile

For Dr. Xiomara Duverger, a Cuban physician from Guantánamo who defected during a mission in Brazil, the decision to leave was deeply personal.

Follow Dr. Duverger’s journey on an interactive map (opens in new window)“I had done everything right,” she said. “Studied, worked, served. But inside I was carrying sadness, a deep longing for something more dignified.”

“We sang the anthem… but we learned about freedom only through silence.”

Xiomara Duverger

Duverger described growing up under intense ideological pressure, with constant surveillance and indoctrination. She recalled the Committee for the Defense of the Revolution monitoring every neighborhood.

“We sang the anthem, saluted the flag and repeated, ‘Pioneers for communism, we will be like Che,’ every morning,” she said. “But we learned about freedom only through silence.”

Her missions in Guatemala, Venezuela and Brazil opened her eyes to what Cuba lacked.

“In those places, I saw poverty,” she said. “But I also saw people who could speak freely. I realized Cuba wasn’t just behind, it was paralyzed.”

During the mission in Brazil, Duverger used the Cuban Medical Professional Parole Program to file for asylum in the United States. That program, created in 2006, was designed to help Cuban medical workers defect. It was quietly terminated in 2017, shortly after Duverger’s application was approved.

“They took our passports. They controlled where we lived. They said it was for our safety, but we knew the truth — they didn’t want us seeing the outside world,” she said.

Arriving in the United States, she faced immediate barriers. Her Cuban medical credentials were not recognized, and she had no money to pursue the licensing exams required to practice. Instead, she cleaned houses and worked odd jobs to survive.

“Every dollar I earned felt like a victory,” she said. “And I would make the same decision again.”

Historical Context

Dr. Jorge Duany, professor emeritus of anthropology and former director of the Cuban Research Institute, has spent decades studying Cuban migration. He identifies six waves of exodus since 1959, each marked by varying degrees of political and economic motivation.

“Exile has always been a form of resistance,” Duany said. “Even when it’s not framed that way, leaving is often a rejection of the system.”

Duany said the July 11 protests and the “Patria y Vida” anthem marked a cultural turning point.

“It allowed Cubans to say they loved their country but still demanded a better life,” he said. “You don’t have to die for your homeland — you can live for it.”

The movement, born in both Havana and Miami, resonated across generations and continents. It signaled a new unity between Cubans on the island and in the diaspora.

“You don’t have to die for your homeland — you can live for it.”

Dr. Jorge Duany

“There has been a renaissance of those emotional and political ties between Cubans abroad and at home,” Duany said. “Especially as more second- and third-generation Cuban Americans remain connected to their roots through language, culture and activism.”

U.S. immigration policies have historically fluctuated in response to Cuba’s political climate. The Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966 allowed Cubans to apply for permanent residency after one year in the United States. In 1995, the Clinton administration implemented the “wet foot, dry foot” policy, which allowed those who reached U.S. soil to stay while repatriating those intercepted at sea. That policy was ended in 2017, coinciding with the rollback of parole programs.

“Every generation of Cubans has had to relearn the landscape of immigration law in the U.S.,” Duany said. “And the result is often confusion and instability for people who are already fleeing instability.”

What Lies Ahead

Today, Cuban migration continues, driven by frustration, fear and fading hope. Many newer arrivals — like Duverger — left behind families, credentials and stability in search of a life where they can speak freely, work freely and dream freely.

“The Cuban government is not helping its people… migration is the clearest symptom of that dysfunction.”

Sebastián Arcos

“I still haven’t seen my granddaughter since she was three months old,” Duverger said. “But the sacrifice was worth it.”

Arcos believes that change must come from inside Cuba. Until then, he said, the world must understand what drives people out — and what it means when they are sent back.

“There is no real reform happening,” Arcos said. “And yet, we’re seeing people deported back into a regime that punishes dissent. That’s the tragedy we need to confront.”

“The Cuban government is not helping its people,” he said. “It’s sustaining itself at their expense. And migration is the clearest symptom of that dysfunction.”

For the tens of thousands making their way to the border, it is a journey of risk and uncertainty. But for many, like Duverger, the journey is also a declaration — a statement to the regime and to the world:

They no longer believe in the revolution’s promises. They are choosing dignity over silence.